|

|

|

This page provides information and a variety of ideas

that might be of use to play therapists. Most are in the form of

brief articles. We try to add new ideas regularly, so please visit

again! To access the ideas, simply click on the titles below.

Electronic versions of these papers and chapters are provided as a professional courtesy to ensure timely dissemination of professional work for individual and noncommercial purposes. Copyright and all rights therein reside with the respective copyright holders, as stated with each chapter or article. These files may not be reposted without permission.

Articles

Play Therapy Ideas Play Therapy Ideas

Play Dough

Recipe

Risë VanFleet, Ph.D

© 2010, Play Therapy Press. All rights

reserved for articles and photographs.

1 1/2 cups water + 2 Tbs. water

1/2 cup salt

1 tsp. food coloring

Mix the ingredients above and put in pan. Heat until it boils. Pour

heated mixture over the following flour mixture:

Flour mixture: 2 1/4 cups flour and 2 Tbs. powdered alum (optional) in

a mixing bowl.

After adding heated mixture, add 1 Tbs. salad oil. Stir all together in

bowl as fast as you can. When you cannot stir anymore, put on board and

knead until mixed well. The play dough does not need to be refrigerated. It

may be stored in a wide-mouthed jar with a tight lid or in a sealed plastic bag.

•back to top

How to Set Up

a Filial Therapy Playroom How to Set Up

a Filial Therapy Playroom

Risë VanFleet, Ph.D

© 2010, Play Therapy Press. All rights

reserved for articles and photographs.

What is Filial Therapy?

Developed in the early 1960s by Dr. Louise Guerney and Dr. Bernard Guerney,

Filial Therapy is a highly effective psychoeducational family intervention

in which

parents serve as the primary change agents for their own children. The

therapist trains the parents to conduct special child-centered play sessions

with their own children, supervises these play sessions, and eventually helps

parents transfer the play sessions to the home setting. The therapist

helps parents understand their children more deeply, explores parents' reactions

and issues, and guides parents in problem-solving. Children benefit

greatly from the play sessions, and parents gain skills and confidence in

the complex

tasks of childrearing.

Filial Therapy can be used as a prevention approach as well

as an effective intervention for a wide range of child/family problems: oppositional

behaviors, anxiety, depression, abuse/neglect, single parenting, adoption/foster

care, relationship problems, divorce, family substance abuse, toileting difficulties,

trauma, family reunification, chronic illness, etc. (Please see the Books & Articles

page of this website for more information).

Setting Up the Playroom: Toys

A Filial Therapy playroom looks much like a child-centered play therapy room. A

variety of toys which can be used in imaginative and expressive ways by children

are scattered in an inviting manner around the playroom. A sample listing

is below:

Family-related and nurturance toys:

• doll family (mother, father, brother, sister, baby)

• doll house/furniture

• puppet family and animal puppets

• baby doll

• dress-up clothes

• baby bottles

• container with water

• bowls for water

• kitchen dishes

Aggression-related toys:

• bop bag

• dart guns with darts (colorful, toy guns)

• small plastic soldiers and/or dinosaurs

• 6-10 foot piece of rope

• foam aggression bats

Expressive and construction toys:

• crayons or markers and drawing paper

• Play-Doh, Sculpey, or other modeling substance

• sand tray with miniature toys

• plastic telephones

• scarves or bandannas

• blocks or construction toys

• heavy cardboard bricks

• blackboard

• mirror

• masking tape

• magic wand

• masks

Other multi-use toys:

• cars, trucks, police cars, ambulances, firetrucks, school buses, etc.

• playing cards

• play money

• ring-toss or similar game

• doctor's kit

Because parents eventually conduct filial play sessions at

home with their own toys, the filial therapist develops a modest playroom. Extravagant

playrooms can unintentionally create pressures on parents to "compete," or

may set the children up for disappointment when they begin their home sessions.

Setting Up the Playroom: Layout

Ideally, the filial therapist would have a playroom

and an observation area with a one-way mirror. This is particularly useful

with filial therapy groups. Since most of us do not operate under ideal

conditions, an alternative is discussed here.

If you have a single room, it can be divided into a play

area and an observation area. (The observation area is used by parents

who watch the therapist's play session demonstrations and by the therapist

as he/she supervises the parent-child play sessions.) In essence, the

observation area is delineated by furniture arrangement. For example,

a desk or table can be placed at the end of the room or across a corner with

one or two chairs on the non-play-area side. The desk or table would

be considered "off limits" to the child during the play sessions

and could be handled with an initial explanation to the child and by normal

limit-setting thereafter.

My current playroom uses about 2/3 of a room. I've

placed a dress-up chest and a toy cabinet across the open end of the room. Once

the child enters the play area, I (or the parent) place a child-sized chair

in the opening we've entered through. On the non-play-area, or observation,

side (the remaining 1/3 of the room), I have a small desk and chairs. It's

clear by this furniture arrangement that the observers are divided off from

the play area.

Even though the therapist is in the same room, clearly visible

to both parent and child during their filial play sessions, I have found that

children are rarely distracted by this. Occasionally, children may turn

to the observing therapist and ask a question. When this happens, I tell

them to check with their parent (affirming the parent's authority over the

play session). I also use peripheral vision as much as possible while observing

so that I remain as unobtrusive as possible.

If you have extremely limited space and cannot have a permanent

play area, you might want to try this idea shared by a therapist who attended

one of my workshops (I don’t recall her name, or I’d give her credit!). She

placed a blanket on the floor and the toys on the blanket. The boundaries

of the blanket became the physical boundaries of the play sessions. When

the play session was over, she simply folded up the blanket with the toys inside

and placed it in a closet until it was next needed.

•back to top

Helping Parents Develop Their Own Toy

Kits in Filial Play Therapy

Risë VanFleet, Ph.D

© 2010, Play Therapy Press. All rights

reserved for articles and photographs.

In Filial Therapy, parents eventually hold play sessions with

their children on their own at home. We recommend that they use a separate

set of toys for these sessions to help communicate the "specialness" of

the play sessions to the child. This brief article discusses ways to

help parents develop a separate toy kit for this purpose.

Early in Filial Therapy, I provide parents with a list of

toys similar to the one above. I ask them to try to assemble these toys

over the next several weeks. I explain that they needn't get everything

on the list, but to try to obtain toys from each of the various sections. As

they near the point where they will be conducting play sessions on their own,

I then remind them again of the need for a separate kit of toys. It's

fine if there are a few "cross-over" toys, i.e., toys which children

use in everyday play, but it's best to minimize this. Common "cross-over" toys

might be a dollhouse or other fairly costly items that can't easily be duplicated. I

suggest that parents keep the toys in a bag or box in a location that will

not be tempting for curious children.

Although the cost of a "starter" play kit is probably

about $150, that's a great deal of money for some. Indigent families

need alternatives to purchasing lots of brand new toys. Parents and workshop

attendees with whom I've worked have suggested many creative ways to assemble

these toys. Their ideas and some of my own are outlined below.

Low- or No-Cost Toy Substitutions

Dollhouse:

• Box with dividers from a grocery store

• 4 shoeboxes glued together to form 4 rooms

• Large box top, piece of cloth, or paper divided into quarters, or rooms

Doll Family:

• Clothespins with features drawn or glued on

• Sculpey figures

Dollhouse Furniture:

• Plastic pizza "stabilizers" (white object used to prevent "slides")

can be used as tables

• Small blocks of wood

• Other common household items - think creatively!

Puppets:

• Socks with yarn hair, button eyes, etc.

• Socks with magic marker features drawn on

• Specialty wash cloths

• Specialty oven mitts

Bop Bag:

• Pillow with face drawn on cover

Kitchen Set:

• Margarine tubs of different sizes

• Divided plastic dishes from microwave or frozen dinners

For homemade items, it's fine to have the parents and children

work on creating their play session toys together. For example, the parent

and child could jointly color the box that will be used as a dollhouse, or

draw the features on sock puppets. With filial therapy groups, it can

be fun to have a toy-making night. It's a nice way to draw out parents'

creativity while developing the toy kit.

Other Sources of Inexpensive Toys

It can also be useful to create some toy kits to loan to parents for their

home sessions. It's nice if parents contribute some of the toys, but

the rest can be loaned to them and returned after they've finished having

home sessions. Toys for these kits can be obtained quite inexpensively

from yard sales and flea markets. You can also circulate a list of

needed toys among coworkers (and other family members' coworkers) and collect

needed items. Some child- or toy-related businesses are willing to

donate toys for such purposes. I've also approached charitable organizations,

presented a brief "seminar" about play therapy and filial therapy,

and then asked them to consider a donation for these toy kits to be loaned

to indigent families. For example, when I worked in a community mental

health center, I gave a talk to a local charitable business organization

that resulted in much interest about play therapy and a $2000 check for toys

for our in-home filial therapy program!

Ideas for developing toy kits are bounded only by

your own and your clients' creativity. I've found that the more you

keep an eye out for ideas for toys, the more creative you become!

•back to top

Personal Storytelling

Risë VanFleet, Ph.D

© 2010, Play Therapy Press. All rights

reserved for articles and photographs.

People have engaged in storytelling for

centuries, long before recorded history. It's a way to pass along cultural

and family practices and values and to create social bonds through a common

history. Various

types of storytelling techniques have been employed in child therapies (VanFleet,

R. (1993). Strengthening families with storytelling. In L. VandeCreek,

S. Knapp, & T. L. Jackson (Eds.), Innovations in Clinical Practice: A Source

Book, Vol. 12. Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press, 147-154.). People have engaged in storytelling for

centuries, long before recorded history. It's a way to pass along cultural

and family practices and values and to create social bonds through a common

history. Various

types of storytelling techniques have been employed in child therapies (VanFleet,

R. (1993). Strengthening families with storytelling. In L. VandeCreek,

S. Knapp, & T. L. Jackson (Eds.), Innovations in Clinical Practice: A Source

Book, Vol. 12. Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press, 147-154.).

Personal storytelling involves the sharing of actual memories

in individual or group/family therapy. Described here is one way of using

personal storytelling with a family in therapy. I ask the family to relax

(closing their eyes is encouraged, but optional). I then ask them to

think about a favorite toy or object from their childhood. I slowly take

them through some simple imagery, asking them to think about what the toy looked

like, how large/small it was, what it smelled like, where it came from, how

they played with it, how they felt when they played with it, any special experiences

they had with it, what happened to it, etc. etc.

Almost invariably this activity evokes memories and feelings,

usually quite pleasant. Next, everyone takes turns sharing their memories

of their favorite toys while the others listen. The therapist can use

the storytelling to help family members understand each other and themselves

better, and sometimes can relate their stories to current-day reactions or

feelings. After each family member has shared his/her story, the therapist

asks them what the storytelling experience was like for them and guides them

as they briefly process the activity.

I use this activity, not for in-depth analysis or insight,

but more to bring families together in a meaningful sharing of their lives. It

should be noted that sometimes sad or angry feelings can be evoked during personal

storytelling, and the therapist needs to leave adequate time for the family

to discuss and work through these feelings.

When there are young children in the family, the therapist

can invite them to tell a story about their current favorite toys. A

subsequent "show and tell" session, if family members still possess

the toys can be fun as well.

•back to top

What

makes strong families? What

makes strong families?

Risë VanFleet, Ph.D

© 2010, Play Therapy Press. All rights

reserved for articles and photographs.

In 1985, Nick Stinnett and John DeFrain published the results

of an extensive research project designed to learn more about the characteristics

that were associated with strong families (Secrets of Strong Families, NY:

Berkley Books). They identified 3000 strong families throughout the United

States and conducted extensive interviews with family members. The families

represented a true cross-section of the population on many dimensions. After

careful analysis, they determined there were six primary features that strong

families have in common:

Commitment

Family members were committed to their relationships and to helping each

member grow as an individual.

Appreciation

Family members frequently told and showed each other that they appreciated

each other, and they were able to be specific about the things they expressed

Communication

These families used good communication skills and they communicated frequently

with each other.

Fun Time Together

Strong families made time together a priority, and some of that time was

spent doing enjoyable, fun things.

Spiritual Wellness

Whether it was involvement in their own respective religious groups or involvement

in inspirational activities such as deep appreciation of nature or music,

strong families reported that their spirituality helped them keep perspective

on the day-to-day stresses.

Coping Ability

When these families encountered tough times, they found a way to pull together

and support each other rather than being fragmented by crises.

Many children and families are resilient,

but in these complex times, sometimes they need a little assistance in overcoming

the obstacles in their lives. One play therapy approach that is designed

to strengthen family relationships directly addresses most of the six characteristics

listed above. Filial therapy, in which therapists train and supervise

parents as they conduct special child-centered play sessions with their own

children, has been shown in 40 years of research and clinical experience

to be highly effective in bringing about long-lasting positive change for

children and parents alike. It can be used individually or in group

formats, for prevention or intervention with serious problems. Families

who have participated in filial therapy often continue their special play

sessions long after formal therapy ends, reporting that both children and

parents truly enjoy them!

•back to top

Combining Nondirective and Directive Play

Counseling in Schools

Risë VanFleet, Ph.D

© 2010, Play Therapy Press. All rights

reserved for articles and photographs.

School settings present many unique challenges to counselors

using play counseling methods. Space and time are often limited. Counselors

may work in several schools and therefore must carry their toys and materials

with them. Children usually must return to the structure of a classroom

immediately after sessions. Time can be seriously limited, and counselors

may be responsible for large numbers of children. This brief article

addresses issues in the selection of play counseling methods, given these

considerations. School settings present many unique challenges to counselors

using play counseling methods. Space and time are often limited. Counselors

may work in several schools and therefore must carry their toys and materials

with them. Children usually must return to the structure of a classroom

immediately after sessions. Time can be seriously limited, and counselors

may be responsible for large numbers of children. This brief article

addresses issues in the selection of play counseling methods, given these

considerations.

Short-term, directive play counseling methods are increasingly

popular because they are effective and they fit more readily within the restrictions

imposed by the school setting. There are times, however, when it would

be beneficial to use nondirective play approaches, such as when the counselor

is unsure of what's really going on with the child, when children resist the

direction of the counselor, when there are serious "control" issues,

etc. Many have found nondirective techniques valuable in establishing

rapport with "hard-to-reach" children. Some school counselors

have found the following ideas that combine nondirective and directive approaches

to be feasible and effective.

If time is limited with a child, e.g., if a counselor usually

has only 6 half-hour sessions allotted per child, it is best to let the child

know that at the start. (The counselor must decide if the needed work

can be accomplished within that time frame or if an outside referral is needed.) Using

poker chips, check marks on a chart, or tickets to show the child how many

sessions are left each time helps make it concrete and more understandable

for the child. Children often have a remarkable ability to do their "work" within

boundaries such as these. At the very least, this gives the child the

option to determine how much to reveal/work through during the allotted time.

When combining nondirective and directive play counseling

methods, it's extremely important to ensure that the child knows the difference. This

prevents confusion for the child and keeps their play communication as open

as possible. Ideally, it's best to hold nondirective play counseling

in a different area from the directive play counseling, but very few school

counselors have that luxury. Another way to handle this it to tell the

child something like, "For the first part of today, YOU may select the

toys and how you'd like to play with them; in the last part of today, I will

select the activities." When changing from nondirective to more

directive play, it's helpful to give the child a chance for closure in their

nondirected play ("Laura, you have one more minute left in your playtime

before I select an activity for us.") and then to reiterate, "Now

we're going to do something I've selected." when starting the directive

portion of the session. Most children seem to respond well to this arrangement.

Is it better to start with the nondirective or with the directive

techniques? Although there might be exceptions, I generally suggest that

school counselors start with nondirective, child-centered play counseling and

end their sessions with more directive play counseling. There are two

main reasons for this: (1) Starting with the nondirective play gives

children a chance to relax and permits freer expression of their own issues

at the start of the session. It's the child equivalent of the adult counseling

lead-in, "Tell me how things have been going for you lately." (2)

Children usually must return from counseling sessions to quite structured classroom

settings. Ending with more directive play interventions helps them make

that transition more easily.

With the difficult problems school counselors face

these days, it's important that they have access to as full a range of counseling

methods as possible. Although circumstances sometimes prohibit the

use of nondirective (child-centered) play counseling, counselors usually

can incorporate it as needed using some of the suggestions above.

•back to top

Designing Your Own Play Therapy Ideas

Risë VanFleet, Ph.D

© 2010, Play Therapy Press. All rights

reserved for articles and photographs.

While there are many wonderful ideas described in the growing

number of play therapy books, it can be both helpful and rewarding to develop

your own creativity and spontaneity with play therapy ideas of your own. Even

if you primarily use child-centered play therapy, there are times when you

may need some additional interventions (make sure to keep the child-centered

play sessions and directive techniques clearly delineated for the child, though!). While there are many wonderful ideas described in the growing

number of play therapy books, it can be both helpful and rewarding to develop

your own creativity and spontaneity with play therapy ideas of your own. Even

if you primarily use child-centered play therapy, there are times when you

may need some additional interventions (make sure to keep the child-centered

play sessions and directive techniques clearly delineated for the child, though!).

The following set of questions can help guide your thinking as you try to design

a play therapy intervention for a child or family or specific problem.

- Determine

the therapeutic goal(s) with the child/family.

- What "traditional" methods

of therapy might apply to this problem/goal?

- What does each "traditional" method

in #2 aim to do?

- How could these be made playful?

• puppets or

dolls?

• imaginary

games?

• board games? (existing

or made up)

• artwork or

craft creations?

• release play

therapy?

• sandtray

methods?

• storytelling

approaches?

Take as an example a 5 year old girl who is stung by a bee

in the front of her house and her fear generalizes to the front porch and front

yard. She refuses to leave the house through the "bee way" (front

door). She throws tantrums whenever her parents suggest she try going

out the front door. Her need to use the back door at all times is time

consuming and somewhat of a nuisance to the rest of the family, and her parents

realize that allowing her to use only the back door may only be reinforcing

her fear and behavior.

- The goal would be to help her

become comfortable using the front door, front porch, front yard again.

- Traditional methods? First, it would be important

for the parents to determine if there were any hives or nests belonging

to "stinging

creatures" in front of the house, and to have them removed (common

sense). Second,

we might use systematic desensitization to help her overcome her "phobia" or

fear.

- What does SD aim to do? By helping the client

learn a response incompatible with her fear (i.e., relaxation)

when in the presence of the stimulus, the therapist helps the client become

desensitized

(less afraid). This is done in a hierarchical fashion

until the client is able to face the actual feared stimulus

(the front

of the house) without

experiencing the fear.

- How could this approach be made playful? Play

might also be considered to be a response incompatible with

her fear. A

game involving a bee puppet could be developed. The therapist

could talk with the child about why bees sting (because they're

threatened or afraid),

and that it might be fun to show the bees that the child isn't

going to threaten them. Using bee puppets (best if the

child and the therapist each have one), the therapist helps

the child practice "being a bee" by flying

the puppet around the room and making buzzing sounds. This

would all be done in a very lighthearted manner, with laughter

and silliness. (Of

course, if the child might be afraid of the bee puppet, the

intervention would have to start with an even less "realistic" approach--a

judgment call on the part of the therapist, although discussing

the puppet idea with

the child first can help with that decision.)

The "Be a bee" game could be played (rehearsed)

for several sessions, perhaps having the child teach her parents how to "be

a bee" as well. Eventually the game could be tried in vivo, either

with the therapist present at the home, or with some training so the parents

would know how to handle the in vivo attempt. Here's how one family handled

it: They made their own bee puppets using yellow socks, black magic markers,

and pipe cleaners. They then let the "queen bee" (their daughter)

lead the way out the front door, with the entire family buzzing along behind

her. They kept it light with lots of laughing, just as they had learned

during the therapy sessions, and after a week of family buzzing, their daughter

grew tired of the game and no longer needed assistance in using the front door!

•back to top

Redefining Resistance in Therapy

Risë VanFleet, Ph.D

© 2010, Play Therapy Press. All rights

reserved for articles and photographs.

Client resistance to therapy can pose serious challenges for

the mental health professional. One step, among many, that we can take

involves examination of our own attitudes about resistance (for a full discussion

on the topic of resistance, please see the Play Therapy Videos page). Reprinted

below is a brief article which can help us redefine resistance in a way which

increases our likelihood in handling it effectively.

Psychological research and common sense suggest that it's

important for people to feel in control of their lives. When control

isn't possible, predictability is a characteristic that helps people cope with

and adapt to situations. When families encounter problems with their

children and/or their relationships with each other, they often feel as though

they have little or no control over their home lives. Furthermore, American

culture emphasizes the value of independence and the ability to handle one's

own problems. Some families may perceive attendance at therapy as a very

visible reminder that they are unable to handle their own problems as they "should," and

that there is something "wrong" with them. This creates an

atmosphere where resistance is possible, and the negativity of this climate

can be compounded by misrepresentations of therapy in the media and even by

some therapists.

The purpose of therapy is to help families change. Although

families may dislike the problems which have brought them to therapy, there

are at least some elements of predictability to the problems (e.g., although

Freddie may misbehave, which may seem out of the family's control, at least

his misbehavior is somewhat predictable for them). The changes suggested

by a therapist sometimes seem like a leap into the unknown, which has no predictability

at all for the family. If therapy helps Freddie change, he may no longer

be as predictable, and if therapy focuses on parents' changing, they may feel

lost in foreign territory. (The predictable nature of the problem may

be preferable to the positive, but unpredictable offerings of therapy.) Regardless

of the situation, families often resist change in order to restore their home

life to it former, more predictable state.

Considering these dynamics, resistance can be seen as a natural

outgrowth of the change process. Expecting resistance as a natural part

of the therapeutic process can help practitioners to handle it more effectively.

Therapists and change agents often become frustrated with

the resistance they encounter, sometimes assuming that parents or family members

are deliberately trying to sabotage therapeutic efforts. While this can

be the case, it is rare. When therapists view resistance as something

that needs to be eradicated, they may unintentionally set up antagonistic relationships

that are inconsistent with the changes they are trying to facilitate. Instead,

it can be helpful for therapists to alter their expectations: to think

of resistance as a natural part of the change process and as an expression

of parents' or family members' unmet needs. This view of resistive behavior

is more likely to help therapists select helpful interventions.

Family members who seem reluctant to embrace therapeutic

changes may be expressing their need for a greater sense of control or predictability,

fears about losing control or independence or status, anxiety about adopting

new roles or behaviors which are not yet clearly defined for them, doubts about

their own ability to carry out changes, concern that the changes might result

in a weaker rather than a stronger family, and other reactions. If therapists

can determine and understand the needs that are being expressed through the

resistance, they are in a better position to help families overcome their reluctance

to make changes.

Frank discussion of family members' concerns should be encouraged. It

is important for therapists to listen without judging family members' reactions

in order to maintain open communication. Patience is also essential. A

climate of understanding can set the stage for more collaborative working relationships

with even quite challenging parents.

•back to top

Play and Culture

Risë VanFleet, Ph.D

© 2010, Play Therapy Press. All rights

reserved for articles and photographs.

When trying to help parents or other professionals understand

play therapy, I've often guided them as they examined how their own culture

or subculture has viewed play. Although I'm sure some cultures may be

more lighthearted and others more serious, since play is a universal phenomenon

among children, there's usually something to be learned from examining its

role in one's own upbringing and/or social world.

There are many different ways to think of culture. Different countries have

different cultures. “Culture” can be strongly related to one’s

race, religion, ethnic heritage, and even generation or age. But there is often

great diversity within these broader categorizations of culture. Each family

has its own customs, beliefs, and practices that could be viewed as the “culture

of that family.” Families are embedded in neighborhoods and communities

that have cultural influences. Even our socio-political environment affects

culture. In graduate school, I was deeply influenced by a child development

course in which we examined the “culture of childhood” that shows

how some games and practices are passed along from one generation of children

to another without adult intervention! In this brief article, I am thinking

of culture from these broader perspectives.

One of my great joys in life is getting out into wilderness

areas and hiking or photographing wildlife in their natural world. That

interest, plus the fact that some of my favorite relatives live there, has

taken me to Alaska on many occasions. I have been fortunate to learn

a little about the Native Alaskan cultures and heritage there. Several years

ago, I had the unique opportunity to attend one of the Inupiaq Eskimo shareholders'

meetings in March. Prior to the business meeting, several

hours were spent in playful activities and games including dogsled races and

Eskimo football (a game in the snow for men and for women that seemed to me

to have one primary rule—players must wear mukluks!). The games involved

the entire community from children to elders. The sense of community

and celebration was wonderful to me, and that cohesiveness then seemed to carry

over into the business meeting that entailed discussion of some very serious

and difficult topics.

On another winter trip, I took part in a traditional blanket

toss. In their native language, they began by saying something like "we

are the community" (they translated from their native tongue for us non-natives). They

taught us that the object of the blanket toss was to get the person high into

the air and then help them land on the blanket (actually a hide) on their feet. That

happens only if everyone is cooperating. Everyone must pull the "blanket" back

with the same amount of energy. If one side is pulling harder than the

other, it's likely that the person being tossed will lose their balance when

they land. If everyone pulls together more equally, a successful landing

on the feet is much more likely. The tosses are accompanied by noisy

encouragement as everyone learns to work together for the same goal. Success

in this "game" requires cooperation rather than competition. And

that value seems to parallel that of the Native Alaskan cultures for thousands

of years, where survival in a harsh environment has depended upon cooperation

and sharing.

I was given a poster entitled "Our Inupiaq Way" that I have framed

in my house. It details the cultural values of the Inupiaq people. Consider

the examples of play that I've shared above in light of these:

Responsiblity to tribe

Knowledge of language

Sharing

Respect for others

Cooperation

Respect for elders

Love for children

Hard work

Knowledge of family tree

Avoid conflict

Respect for nature

Spirituality

Humor

Family roles

Hunter success

Domestic skills

Humility

As a Filial Therapist, I was struck by the consistency of

these values with those of the Filial Therapy method! We have similarities

and differences with all of our clients, and it is through respectful dialog

with our clients about their cultural experiences and their attitudes toward

play that we can develop a therapeutic partnership that is much more likely

to serve our clients well. It has been enjoyable and informative for me to

learn more about families’ play experiences, and I believe their reflections

on the topic have helped them understand more about the value of play in their

children’s and their own lives. I would recommend the work of Dr. Brian

Sutton-Smith to those interested in this general topic!

It can be an interesting and informative journey to explore

the development of one's attitudes about play. Taking the time to do

so in the context of the parents' own experiences and family’s culture

and heritage can help them understand why play therapy might be a beneficial

treatment for their child or family. It can also help us to understand

our clients' uniqueness and the special experiences--good and bad--they bring

to the therapy process.

•back to top

Helping Children and Families Through Traumatic

Events

Risë VanFleet, Ph.D

© 2010, Play Therapy Press. All rights

reserved for articles and photographs.

If you go to the Parents' Page of this

website, you'll find a section on how parents and caregivers can help children

through traumatic

events. I've also included there a list of signs to watch for that

might indicate that a child has been traumatized. Since many of us are

involved in treating children who have been exposed to trauma, either directly

(or indirectly through the news media), I thought it might be helpful to have

a few resources at our fingertips. The list below is far from exhaustive,

but I've found these resources to be useful. If you go to the Parents' Page of this

website, you'll find a section on how parents and caregivers can help children

through traumatic

events. I've also included there a list of signs to watch for that

might indicate that a child has been traumatized. Since many of us are

involved in treating children who have been exposed to trauma, either directly

(or indirectly through the news media), I thought it might be helpful to have

a few resources at our fingertips. The list below is far from exhaustive,

but I've found these resources to be useful.

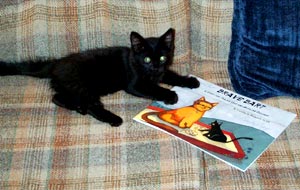

Brave Bart by

Caroline Sheppard (illustrated wonderfully by John Manikoff) is a wonderful

children's book about

trauma and grief. Bart is a cat who has been through a "very bad,

sad, and scary thing." He has some post-trauma symptoms, which are

explained in simple language in the book, and then he explains how he was able

to overcome them. I particularly like this book because it does not label

what the bad, sad, scary thing was, so it can be used for children experiencing

all kinds of trauma. Children have responded exceptionally well to this book,

and it is probably my favorite children’s book about trauma.

When Something Terrible Happens by

Marge Heegaard is a workbook for children (useful with adults, too) that helps

them express their feelings about a traumatic event and helps them determine

coping strategies. It "walks them through" the process of grieving

and recovery. There is space for children to draw, color, or write in

response to a question or cue on each page. This book, also, does not

specify the trauma and can be used for many different situations.

Too Scared to Cry by

Lenore Terr is an important resource book on how children respond to trauma. Based

upon her research with the child survivors of the Chowchilla bus kidnapping

and many other trauma cases, the book provides a close look at the signs of

trauma reactions and the devastating and lifelong impact trauma can have if

unnoticed or untreated. This is one of my favorite books for professionals

who work with children and trauma.

Play Therapy for Psychic Trauma in Children by

Charles Schaefer (a chapter in the Handbook of Play Therapy, Vol.

2) provides excellent information about the impact of trauma on children and

how play therapy can be used to treat it.

Rubble, Disruption, and Tears: Helping

Young Survivors of Natural Disaster by Janine Shelby (a chapter

in The Playing Cure) provides excellent information about the

impact of natural disasters on children and how play therapy can

be used to treat it. Much of the information is also applicable to

man-made disasters and other traumatic events. Her focus on developmental

aspects of trauma intervention is excellent.

Filial Therapy for Children Exposed to Traumatic

Events by Risë VanFleet and Cynthia Sniscak (a chapter

in the Casebook of Filial Therapy) discusses the value and application

of filial therapy with children and families experiencing traumatic situations.

It includes adaptations to the filial therapy process for this population.

Another source of information is the National

Institute for Trauma and Loss in Children, based in Michigan.

Most of the resources listed above are

available from a variety of sources, but I know that the Self-Esteem Shop

carries them, as well as other

useful materials. They can be reached at www.selfesteemshop.com or

at 800-251-8336.

Play therapy and filial therapy can be

extremely helpful to traumatized children and families. They should be conducted

only by professionals

with appropriate training, supervision, and experience, however. The Family

Enhancement & Play Therapy Center offers trainings and consultation/supervision

on the use of these approaches for trauma. A new book, Play Therapy

for Traumatic Events by Drs. Risë VanFleet and Heidi Kaduson,

is in process.

•back to top

Filial Therapy Research Outcomes

Risë VanFleet, Ph.D

© 2010, Play Therapy Press. All rights

reserved for articles and photographs.

Filial Therapy was created in the early

1960s by Drs. Bernard and Louise Guerney, and extensively researched and

developed by Dr. Louise

Guerney and others for the past 40 years. Filial Therapy is a psychoeducational

intervention in which the therapist trains and supervises the parents as they

hold special child-centered play sessions with their own children (ages approx.

3-12), thereby engaging the parents as partners in the therapeutic process

and empowering them to be the primary change agents for their own children. A

combination of family therapy and play therapy, Filial Therapy aims to eliminate

presenting problems, improve parent-child relationships, and strengthen the

family system as a whole.

Filial Therapy has been used successfully

with many child/family problems: aggression, anxiety, depression, abuse/neglect,

single parenting, adoption/foster care, relationship problems, divorce, family

substance abuse,

oppostional behaviors, toileting difficulties, attentional problems, trauma,

chronic illness, step-parenting, multi-problem families, etc.

Filial Therapy has been researched a great

deal. This

summary outlines the results of published and unpublished research, including

academic research, doctoral dissertation research, and data collected in community

mental health and independent practice settings.

Filial Therapy study findings over the

past 40 years are very consistent. The following significant gains

are frequently noted

- Therapy drop-out rates are low

- Children's presenting problems improve or

disappear\

- Parents' skill levels improve (knowledge and actual use)

- Parents' acceptance & understanding

of their children improves

- Parents' stress levels decline

- Parents' satisfaction with results is very

high

- 3- and 5-year follow-up studies have shown that these gains are maintained

A review of the Filial Therapy research is available in the

following reference:

VanFleet, R., Ryan, S.D., & Smith,

S.K. 2005. Filial

Therapy: A Critical Review. In L.A. Reddy,

T.M. Files-Hall, & C.E. Schaefer (Eds.), Empirically-Based

Play Interventions for Children (pp. 241-264). Washington,

DC: American Psychological Association.

•back to top

Gaining Knowledge/Credentials in Play Therapy

Risë VanFleet, Ph.D

© 2010, Play Therapy Press. All rights

reserved for articles and photographs.

I have posted some information about credentials

on the Parents section of this website. The information below is provided

to help professionals

determine how they can develop their knowledge and skills in the field and

some of the credentials that are available. Most of the information provided

relates to play therapy education and credentials in the United States, although

I’ve included a little information about international opportunities.

Although there are a few graduate programs

and post-master’s

qualifying courses in the United States and other countries that offer significant

numbers of courses in play therapy, it's more common for a college or university

to offer just one or two courses, if that. There seem to be more courses

being offered as the demand for play therapy education increases, but it's

still difficult to find substantial university offerings. (If you're

considering graduate education that would provide a great deal of play therapy,

please contact the Association

for Play Therapy in North America or the British

Association of Play Therapists in the United Kingdom. As I become

more familiar with other countries’ play therapy training options, I

will try to update this information here (also, please watch our International

page for information about this). I expect this will continue to

change for the better, but it will take time.

Most people take what courses they can

during their graduate programs and pick up the bulk of their play therapy

education from workshops

and conferences--either during or after they've completed their university

training. I usually recommend that people pursue their master's or doctorate

degrees in programs that increase their ability to practice independently (if

that's a goal for them). In the U.S., each state has its own licensing

laws, so it's best to research which types of degrees are eligible for licensing

in your state. For example, most states license doctoral level psychologists;

some license master's level psychologists. Most states seem to license

master's level social workers; some (but not all) states license counselors

and marriage and family therapists. It is the license in these broader

professional categories that permits you to practice independently (within

the scope of the license). Play therapy is considered a specialty within

these broader areas, so there's no "state license" to practice play

therapy. (You can become a licensed psychologist or licensed social worker

who specializes in play therapy, however.) In some countries, there IS a separate “license” or

credential as a play therapist that is comparable to a psychologist, counselor,

or social work license.

There are several credentials that play

therapists in the U.S. can pursue to demonstrate to the public and other

professionals that they

have received special training in play therapy. The Association

for Play Therapy offers the "Registered Play Therapist" and the "Registered

Play Therapist-Supervisor" credentials. Being an RPT or an RPT-S

means you have achieved a certain level of training and supervision in play

therapy. If you are (or will be) a master's level mental health professional

who seriously wants a career in play therapy, I'd suggest you contact the Association

for Play Therapy and request their full application packet to become an

RPT. You will be able to see the types of training, supervision, etc.

that are required.

Other organizations, including my own,

offer other play therapy credentials. Each of these is designed to show that you have achieved

at least a minimum degree of training/supervision in the field. The "Filial

Therapy Certification" that is offered by the Family Enhancement and Play

Therapy Center is a specialty certificate program. (Many of the requirements

overlap with those for the Registered Play Therapist, so you can work on the

two different credentials simultaneously.) This certificate, described

elsewhere in this website, is specifically for professionals who use Filial

Therapy and wish to demonstrate their experience and competence in that arena. I

usually recommend that play therapy professionals consider working toward the

RPT credential, developing their sub-specialty credentials either at the same

time or after receiving the more general play therapy credential. Others may

find it beneficial to earn the Filial Therapy Certification initially—it

simply depends on your professional goals.

Perhaps you're not interested in all this "credential" stuff. In

that case, you're still free to pursue further education in play therapy from

workshops and conferences. Increasing numbers of organizations are offering

play therapy training throughout the world. A few distance-learning opportunities

in play therapy are available now, and I expect that will increase in the coming

years.

Play therapy is gaining international momentum, probably because

it works so well, and educational opportunities in the field are bound to increase.

By early 2006, this website will include information about an international

collaborative organization that will provide more information about play therapy

and filial therapy throughout the world.

•back to top

Play Counseling in Schools

Risë VanFleet, Ph.D

© 2010, Play Therapy Press. All rights

reserved for articles and photographs.

Throughout the U.S., school counselors, especially

at the elementary and middle-school levels, are increasingly using play counseling

to help students overcome obstacles to learning. One of the primary reasons

for this is the efficiency and effectiveness of this type of counseling. This

monograph provides a basic description of play counseling, the rationale behind

it, the various forms it can take, and the research that has clearly demonstrated

its effectiveness.

Play counseling is an established intervention

that involves the systematic use of play methods by a trained counselor to

bring about improvements

in the student’s ability to perform nearer to optimal levels at school. The

counselor uses play-based interventions to...

• communicate with students

• help students build a wide range of skills

• improve students’ adjustment to classroom and other school environments

• improve peer relationships

• prevent bullying, school violence, and other serious problems

• address the needs of at-risk students

• remove emotional and behavioral obstacles to learning.

In essence, play counseling stems from the broader field of

play therapy, but tends to use the shorter-term interventions that are appropriate

to the education-related goals that school counselors work toward with identified

students.

Rationale

Play counseling is frequently the most appropriate and effective approach for

several reasons:

- Until students are approximately 12+

years old and develop the ability to use cognitive reasoning more fully,

they tend to process information

and develop their physical, mental, and social skills through their use of

imagination and play. Although child students can talk and “reason” to

some extent, their primary way of understanding the world is through their

playful interactions with it. Play counseling is developmentally-attuned

because it capitalizes on these mechanisms.

- When confronted with problems that interfere

with their learning, students frequently become resistant, withdrawn, ashamed,

oppositional,

helpless, defensive, etc. Play counseling provides an excellent way

to avoid or overcome these emotional obstacles to progress.

- There is considerable research that

shows that children learn best in hands-on, activity-based, and playful

situations. Play

counseling creates those types of learning opportunities in order to reach

its goals.

- Play counseling can be used in conjunction with other counseling

methods, such as behavior management, parent and/or teacher consulting, classroom

guidance, outside therapy.

- Because of its developmental and learning focus, play counseling

is more likely to address the root cause(s) of student problems.

Forms of Play Counseling

There are many different types of play counseling, but most school counselors

select methods which are relatively short-term and focused on the more specialized

goals of a school guidance program. For example, Adlerian play counseling

and cognitive-behavioral play counseling approaches are commonly used in

schools. Shorter-term forms of child-centered play counseling and social

skills interventions are also effective. Dramatic play counseling is

a form of behavioral rehearsal that helps students learn to behave more assertively

or prosocially, as needed. Play counseling offers individual, group,

and classroom formats that are easily adapted to meet specific student and

school needs.

Research

A considerable amount of research has been conducted on the effectiveness

of play counseling. Results show quite consistently that it typically yields

significant positive changes in children/students. For example, one study

showed that children with ADHD improved in nearly all problematic areas following

a systematic set of interventions using play counseling. These improvements

carried over into “real life” and were noted on commonly-used teacher

and parent rating measures.

A recent meta-analytic review of play therapy

and play counseling research has shown it to be very effective in addressing

child and student

problems. Because students can develop new skills, new ways of interacting,

and new attitudes through play counseling, its results can be long-lasting. Of

course, the results are much stronger when the counselor keeps teachers and

parents informed of progress and assists them with other interventions that

might be useful in the classroom and at home. A “team” approach

can enhance any school counseling program.

In schools where the counselor initiates

the use of play counseling, it is quite common for teachers to comment to

the school counselor, “I’m

not quite sure what you’re doing, but it’s working!” Play

counseling does not solve all problems, but it represents an effective intervention

that school counselors are employing more and more frequently.

A Few Examples...

- Play counseling helped an anxious, perfectionistic

student take more risks in her schoolwork, improving her performance

which had suffered from her

excessive fear of making mistakes.

- Play counseling helped a disruptive

student cope more effectively with his angry reactions to his parents’ divorce

so that his outbursts, “talking-back,” and

general “acting out” on the playground, on the bus, and

at lunch were virtually eliminated.

- Play counseling has been extremely

effective in the aftermath of several

high profile and tragic school violence incidents. It has been

used to help students express their fears and other reactions to

such events and to return

as much “normalcy” to the school environment as quickly

as possible.

- Play counseling has been used to help a selective-mute

student talk with her teacher and participate in classroom discussions

once again.

- Play counseling helped an entire class welcome a badly

burned and scarred student back to school without undue embarrassment,

while helping

classmates explore their attitudes and beliefs about handicapping conditions.

- Play counseling has been used to help ADHD students increase attention

span, stay on-task longer, and be less distractible in class.

•back to top

|

|

|

|

©

2020 Family Enhancement and Play Therapy Center. Photos courtesy Risë VanFleet.

Copyright

Statement:

Photographs are classified as intellectual property that is protected

by United States copyright laws and internationally by the Berne Convention.

Unauthorized use of copyrighted material is illegal and an infringement

of copyright laws. This web site and all photographs contained within

this web site are copyrighted and may NOT be used, reproduced and/or

copied in any form, including electronic (scanning, altering, etc.),

without

written permission from Family Enhancement & Play Therapy Center,

Inc./Play Therapy Press which represents the photographic and written

work of Risë VanFleet, Ph.D.

|

|